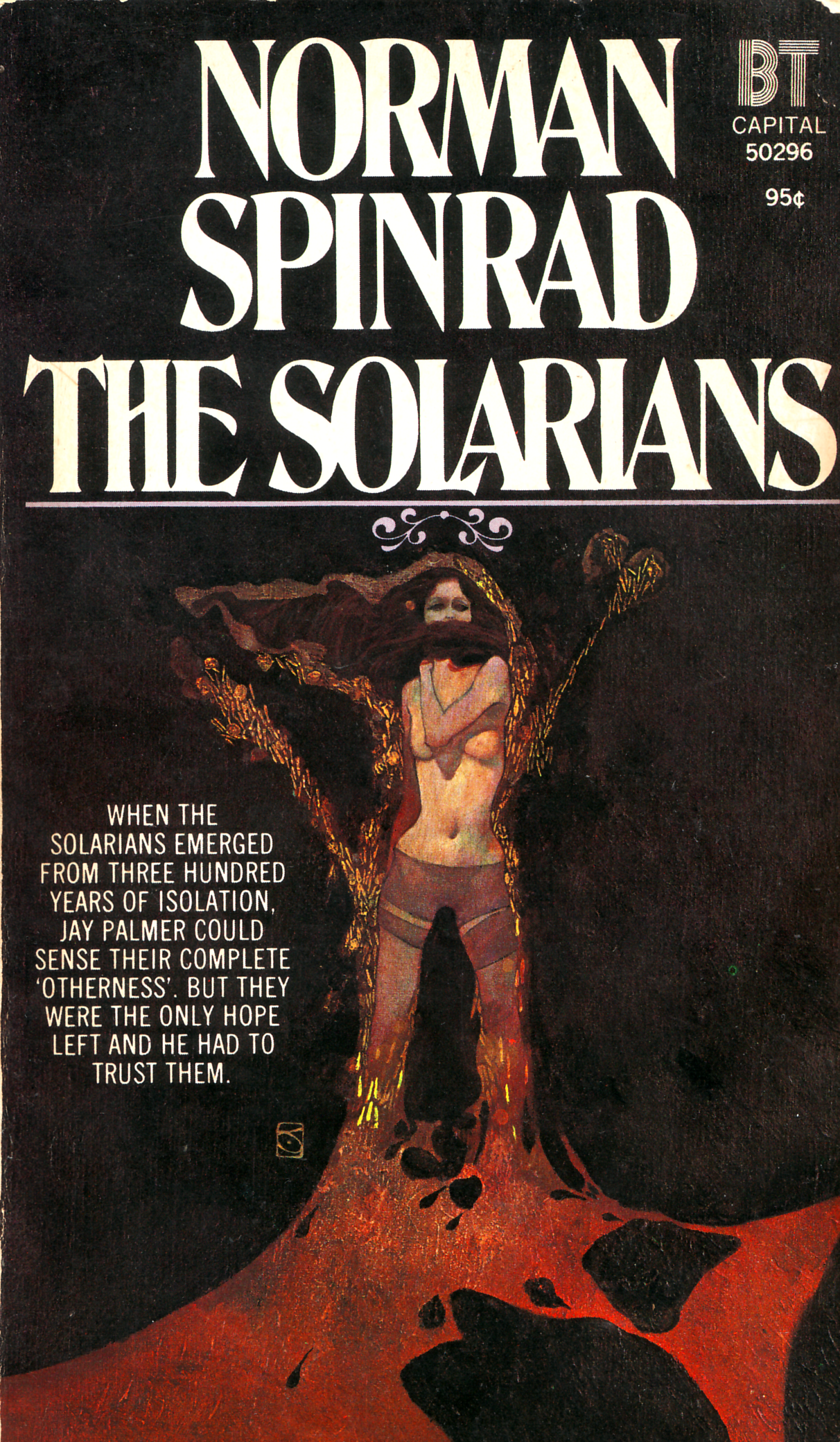

Tangent Futures - THE SOLARIANS (1973) Norman Spinrad

Computers suck

THE SOLARIANS (1973) Norman Spinrad

This is a really decent book, and worth reading. Spoilers mostly limited to the first half or so.

In the future, humankind is locked in a bitter war of attrition, that it is slowly losing. In a century, the centralised computer projects, they will lose completely. Their enemy, the logical and ruthless Duglaars, will achieve their goal and exterminate humanity.

Jay Palmer is our protagonist. He's a fleet commander, though he's hamstrung, because all aspects of tactics and strategy are dictated to him by the central military computers. We find him in the midst of a battle, a battle that is rote and repetitive. The central computer always has the same tactic. Fight, lose, and then retreat.

They put up with this because of "The Promise", made by the leader of Fortress Sol centuries ago. Then, Fortress Sol withdrew from the human Confederation of hundreds of star systems, and closed its borders. In three hundred years, he promised, Fortress Sol would return with something that would turn the tide of the war.

The entire military strategy, for centuries, rests on this premise. To give Fortress Sol enough time and hope they return.

The Solarians return, and have a plan to end the war. They, and their plan, are not what anyone expects...

The narrative is written around Jay Palmer. He's open minded enough, far more than his superiors, and its hinted, more than a lot of people. He's likeable enough, and has a decent internal dialogue, though he has a habit of shouting in surprise when presented with ideas that are new to him. There's a lot of these.

It follows his thoughts and feelings at length, a touch I appreciate in any book. In encountering alien cultures, he only occasionally slips into angry denial, and its usually with a reasonable thought process behind it. At first he conflicts with the Solarians he accompanies, and is distrustful, and that part feels a little contrived and unconvincing, but it doesn't pull the story down too hard.

It's a tightly written book as well. Spinrad is something of a sci-fi heavy hitter, and the talent comes through with how engaging it is. It gets the limits of a pulp sci-fi book, doesn't rush everything at the end (a common mistake), or leave gaps where you want to know how people are feeling.

The Solarians, and the book, is enjoyably, thoroughly anti-computer. As it should be. Computers suck. Humankind, faced with a completely logical enemy, sought to emulate that enemy as thoroughly as possible. The Solarians argue that this strategy was always going to fail, that they should have used their imagination, creativity, their 'alogical nature' as the book puts it. The only outcome was going to be a slow, losing attrition to a numerically superior enemy.

The Solarians fly without a computer onboard, relying on what sounds like a analogue visual fx machine for their star navigation, which is a vision of the future we all aspire to. They live in an old fashioned luxury - books, records, fancy weird future drinks, but no technology. I get this. Its actually totally refreshing to read in a sci-fi novel. Science fiction is littered with starry eyed but unreflective visions of technology. Its one of the few books that has the idea that improving the human condition means disposing of the technology, or at least picking it carefully.

The Solarians argue that we all lose something by adopting computer technology, and this is an idea that resonates far more vividly now. Our own society quietly turns over not only bureaucratic or administrative overhead to computers, but in the past few years, entire job roles. In a primitive way, society is starting to let computers do its thinking for it. In the book, the Confederation has turned over all its planning to computers.

Without really getting too heavy or deep about it, the book manages to articulate the problems with this approach. It argues that humanity is severely hampered by this, that it negates special qualities we possess, and suppresses powers within ourselves that we are just on the verge of being able to use. It is those powers which the Duglaars fear most.

With the Solarians, these powers are advanced and well developed. In a more shrouded way, these apply to us as well.

It quietly makes an argument that should be made today - when we mechanise ourselves, or our society, we become more mechanised in our thinking. Its a bargain we strike with technology, but it has a price. In the book, its fun to see the duality between the Solarians, who didnt make the bargain, and the humans who did. It could be done better though. Palmer has a fault in this narrative, in that he's too skeptical of the computers to really act as an example of a mechanised human.

The Solarians also detest ugliness, utility, pure functionality. They find the militarised, utilitarian nature of the Confederation completely distasteful. To Palmer, whose lived his whole life in a military industrial society, the Solarians live in astonishing luxury.

Socially, they exist in what they call Organic Groups, a sort of chosen family, in this case six members. There's no traditional jealousies or possessiveness, or really for that matter, monogamy. It's not done tastelessly or with awkward horniness. Its also not nearly as transgressive as it would have been in the 1970s. Its perhaps a bit misty eyed about the idea, but its a good underline to how different the Solarian culture is.

Its refreshing to read a book that can effortlessly traverse fifty years, and without knowing it, apply critiques that are more applicable now than in the time it was written.

This book isnt a treatise by any means. Its not a clunky, barely fictionalised depiction of a better way of being. It fits into a narrative quite capably, its just the questions it asks are interesting.

Palmers skepticism in the book is overcome by events proving the Solarians right. Their plan will help humanity win the war, but ultimately humanity needs to change. To embrace its alogicality, its weird and incredible potential. To do away with mechanisation of its culture and thinking, and to become something better. The Solarians are proof of what the species is capable of, and Palmer is there as a gap between them and the mechanic human culture he came from.

As a society, one of the propaganda that is aimed at us is the necessity of function. Its okay if its ugly, we are told, because it serves a purpose. So society litters itself with ugly, identikit things that serve only function, from drive thrus to wind turbines. Beauty is possible, but its often subsumed by economy. We fill the ground and the seas with refuse, because its cheaper than recycling. Economics acts as a false explanation for ugly, low vibe outcomes.

This is often an argument technology makes as well. Both ideas are the products of the same vein of thinking, one that dates to the start of the industrial revolution. Yes, there's good outcomes as well as bad. Yet ultimately, is it just a reductive way of being? Is progressivism an impediment to actual improvement? Is society making a sort of careless bargain, trading agency for mechanical efficiency?

Perhaps question we need to ask is, are the things we're told are necessary, actually needed at all? If it doesn't add to the beauty, happiness, and improvement of the condition of life, human and otherwise, then is it worth persuing?